How to Write a Literature Review

One thing you’re probably going to need to know how to do in your undergraduate career and maybe your graduate school career is write a good literature review. I learned how to properly set up a system to do this from one of coolest profs I had the pleasure of taking a class with at York University, Dr. Jennifer Hunter, MSW, PhD.

A couple of things she taught us really stuck with me and I still use these tips for writing papers to this day so I wanted to share!

1. The first thing to start with is of course finding quality sources. You might have a requirement that sources be within a certain time range (eg, not more than 5-10 years old), or focus on a certain topic. Find out how many are required, or set your own goals, and get researching. Ideally, you want to collect some reference material that is very specific to the idea you are writing about. As closely related as you can get it.

Narrowing down your topic to a pinpoint would be ideal so that you are not just writing in broad generalities. For example, if you wanted to focus an essay on the link between creativity and mental health, ask yourself, what type of creative activity? What definition of mental health? In this example, you could narrow your topic down to the connection between knitting and a reduction of anxiety symptoms.

If you’re not really sure how to gather sources or get good ones, absolutely check if your school’s library can help you. Most will run workshops on these types of things, and most will have very friendly librarians and writing center helpers that would be happy to meet you and explain all about it. I was very lucky in that I had some professors actually show us during lecture how to find the best sources with our school’s resources, but not every professor will do this. Most will probably assume you know how to find sources on your own, and you should.

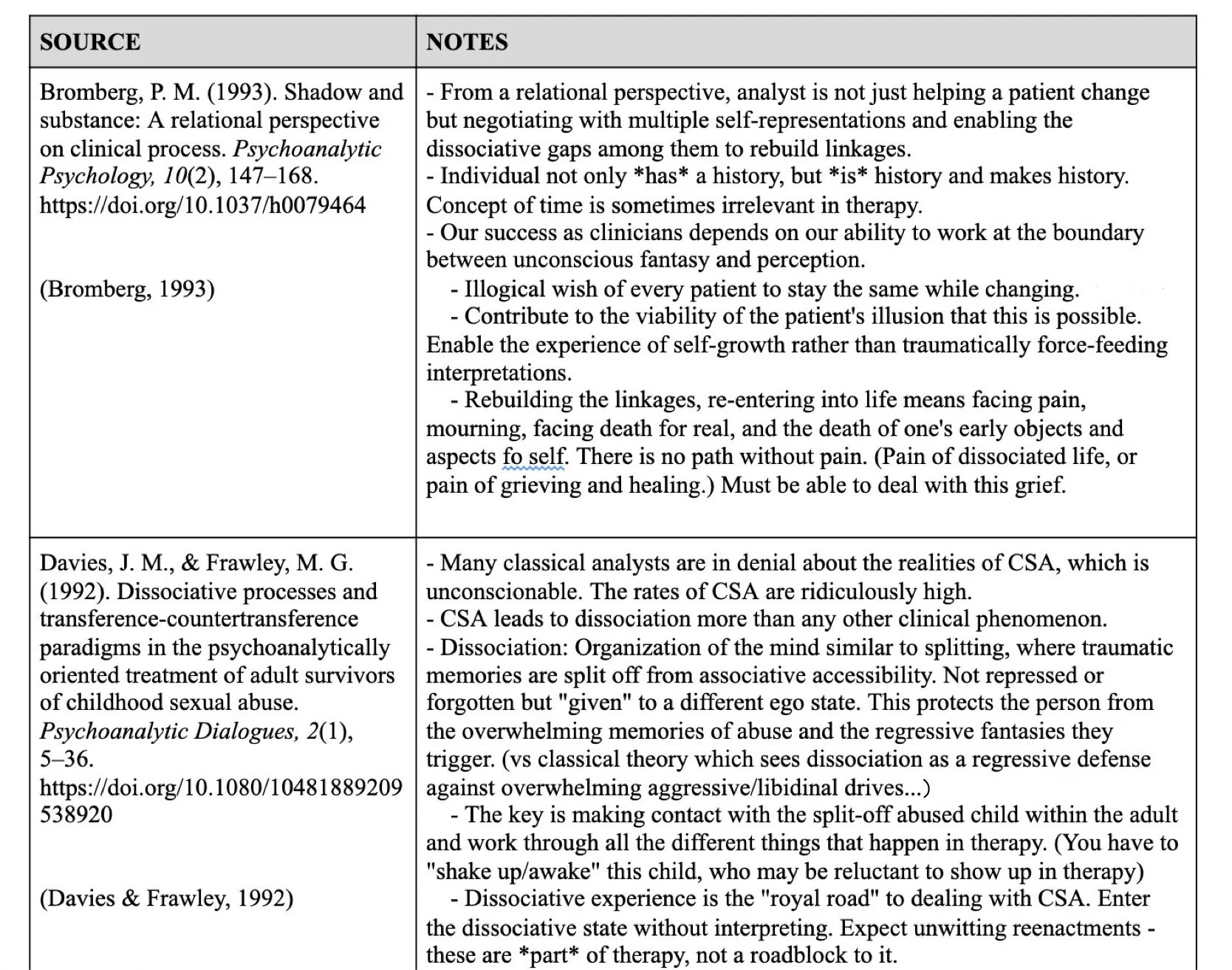

2. Have a system for taking notes. This is so crucial for saving time later on. What I do is set up a spreadsheet in a Google Doc, with 2 columns and however many rows you need (depending on how many sources you are summarizing). On the left side column, write the citation of the article exactly as it will look in your references page, and on the right side make notes about the article in your own words. Lazily copying and pasting quotes from the article will not as much help as being able to explain things in your own voice, plus you won’t have to worry about accidentally plagiarizing later on.

Below is an example of a spreadsheet I started for a recent paper about dissociation through a psychodynamic lens for my final paper in my psychodynamics class. I also included what the in-text citation would look like in the left-side column for easy reference while I am writing my paper.

I prefer to read articles on my iPad, using GoodNotes5. I highlight and annotate the article, then type my notes into this spreadsheet on my laptop.

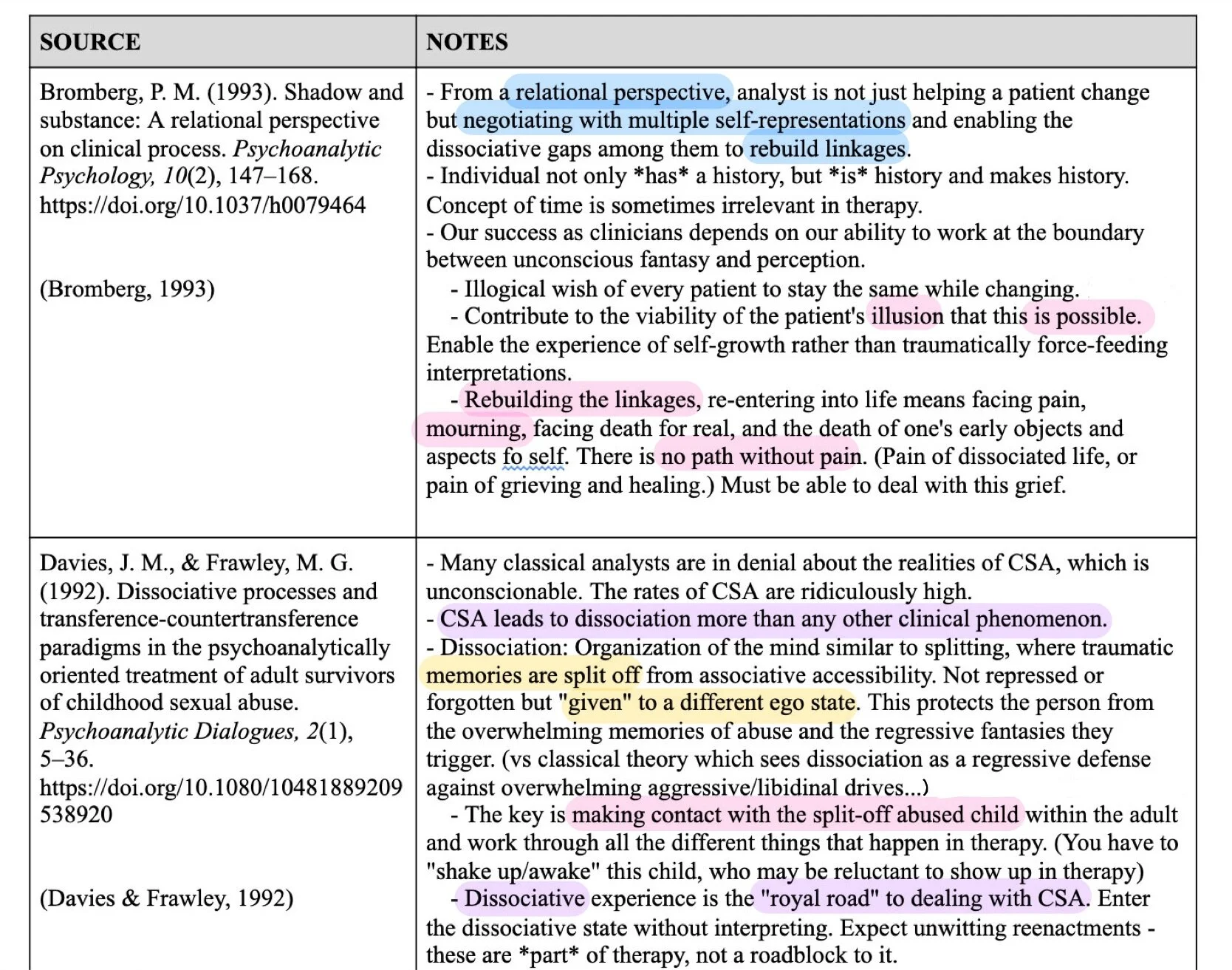

The next step after collecting enough references and enough information from each reference would be letting that sit for a day or two and coming back to it with fresh eyes to start colour-coding your notes. You want to look for main themes across all of your sources.

Ideally, you want to look at the information you have gathered in a new way. For me, that means taking this big spreadsheet I created on my laptop on Google Docs and sending it as a pdf back to my iPad to read it again on a different screen. If you don’t have a tablet, it would also work really well to physically print your notes and highlight them that way. For whatever reason, it just helps to see the information in a new light if you’re not staring at the same screen you wrote it on.

Below is an example of how my spreadsheet would look after highlighting and devising a colour code:

Colour Coding:

Here I’ve noticed some common themes across papers that I may decide to turn into headers or topics to touch into for my paper.

I highlight them in their own colours and then when I am writing for each section of my outline, I can skim through and select quotes and information to cite for each topic.

After you have all of this set up, the writing is way easier!

The next step would be to create an outline. I like to set up my title page, outline, and references page to get some momentum going. You can create headers for each of your main colour-coded topics to gather your notes in each section. Then start writing.

It’s best not to worry about creating a perfect title for now, just write a boring placeholder like “Psychodynamics Final Paper” until you’re further along and have some main themes coming through. Likewise, don’t start on the introduction or conclusion/discussion sections until the end. The best place to start writing would be whatever section seems easiest to finish. Once you have your body sections done, the beginning and end will be much easier to write. You can only tie up the loose ends and highlight your main themes once you know what they are.

Pluck out the most important points from your highlighted notes that correspond to each section. Keep in mind that you don’t want your own voice to get lost among too many quotes and citations, however. Make sure you’re still connecting thoughts in your own unique way.

Just take the writing step “bird by bird,” section by section, crappy sentence by crappy sentence. Don’t worry about whether each line or turn of phrase is perfect - it won’t be and it’s a waste of time to worry about that right now anyway. (You might end up cutting that sentence or paragraph you spent 10 minutes “perfecting” before the editing process is through.) Your job in the initial writing phase is to create a shitty first draft that you can finesse later. You can make notes to yourself as you go, for example using comments on your Google Doc to note where to improve transitions, clarify, elaborate, etc. But don’t worry about actually doing that part as you go along. Just fill out your topics on the outline and get your citations in where you need them.

3. Editing. Once you have your first draft done, take a breath! Take a legitimate break and step away from what you’ve written for a day or two so you can look at it fresh next time. What you did was a real accomplishment (as the Facebook motto goes, “Done is better than perfect!”), so replenish yourself by actually doing something fun that you wished you were doing while you had to write that wretched paper.

Later, come back to your draft and edit with these questions in mind:

Does this flow? Do I have a coherent narrative that winds through the entire paper, or can I create one?

Can I narrow down my topic any further and cut any useless filler to elaborate on what’s important?

Have I integrated across sources, drawing information from all of them to make my points, rather than just summarizing a list of papers I read? (It is not interesting or sexy for a paper to read “this author said this, then this other author said this, then this other third author said this” - connect the ideas with your own ideas and show how all the research works together! Show how the themes/strands flow across papers.)

How are your transitions? Hopefully each paragraph thoughtfully flows into the next and you are not always using the same transition words throughout.

Ask yourself “so what?” With every paragraph or citation you include, make sure you understand what it adds to the paper. Why does the reader need to know this? If it’s not actually that important, consider cutting it.

Finally, check your APA formatting. Are your in-text citations and reference list in line with the latest guidelines? Does your reference list have the proper hanging indent? Cover page and page numbers?

If you’ve done all this, you’ve probably got a pretty decent paper! Be proud of your hard work. Seriously, if you think your paper is interesting and well-written at this point, don’t be shy about seeing if you can include it in a student research fair or turn it into a less formal article for the student paper at your school. Perhaps you could post it to your LinkedIn profile or personal website and start building a portfolio of your academic work for future applications to research lab positions, graduate schools or academic jobs.